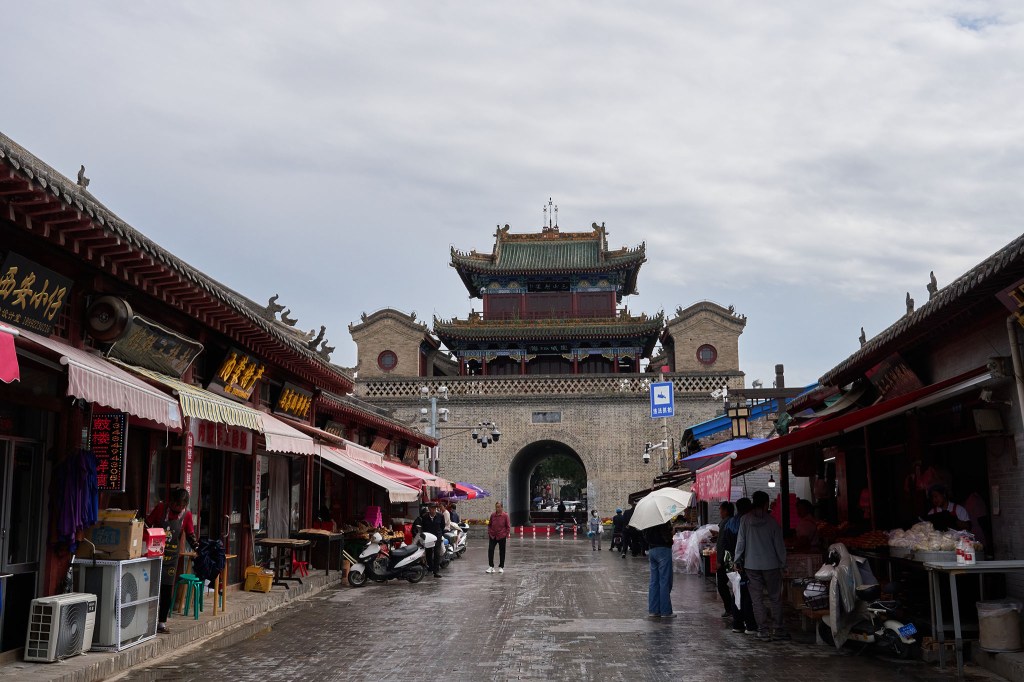

Recently we took a short trip to Yulin, a small city in northern Shaanxi Province. Historically, Yulin served as a frontier outpost in northern China and it still preserves old city walls and ancient buildings now.

Especially the Yulin Grottoes, which are a group of grottoes built on red cliffs, left by Buddhist believers and border guards from different dynasties. Although not as large in scale, famous for statues or murals as the Mogao Grottoes and Dunhuang Grottoes, it is still worth visiting. By reading the Chinese calligraphy above, one can understand the beliefs of those who were once far from the center of the country towards the nation.

Of course, there is another cultural heritage that attracts us, which is Yulin tofu.

Yulin tofu has been recognized as an item of intangible cultural heritage. Among China’s many regional tofu traditions, it holds a distinct reputation.

In China, tofu is generally divided into the southern and northern styles. But in fact, there are more nuanced categories, especially when it comes to the kind of water used in the making process.

In some regions, the well water or spring water naturally contains high levels of mineral salts, which alone can serve as the coagulant, and the byproduct—called jiangshui (fermented or not), the brine filtered out from the last tofu production—is then used again for the next batch.

In this way, it results a kind of tofu that is both firm and tender, with a subtle acidity and lingering sweetness—somewhat like how sourdough starter acts in bread. Traditional Yulin tofu belongs to this family.

The simplest way to find authentic Yulin tofu, of course, is to head directly to the old street. There are two tofu shops there. One is more like a showroom for tourists. The other, which served the local residents. We choosed the latter.

As we stepped inside, a customer was leaving with a bag of large tofu blocks.

The shop was run by a middle-aged man, who, upon spotting us as new, proudly introduced his tofu: As the inheritor of Yulin tofu craftsmanship, his tofu is made from local black beans and old spring water.

The space felt more like a workshop than a store: machines, vats, and tubs for making tofu were all in place. Though the production of Tofu for the day had already ended up.

Some thick tofu chunks with a faint yellow color were placed flat on the table. Can we eat these tofu directly?

When he immediately said yes, we were surprised. He picked up a piece, sliced it into small cubes right in palm, and offered it to us.

At home, we often taste freshly made tofu the same way. But eating it directly from a stranger’s hand in an old-fashioned workshop, was the first time.

The tofu was still warm. It carried a faint bean aroma, a gentle acidity, and—amazingly—the more we chewed, the sweeter it became. It reminded us of soft steamed eggs or even a creamy milk pudding.

Then the shop owner suggested: ‘Let me make you a dip with jiangshui. That’s how we locals eat it.”

From a rice cooker, he ladled out some of the tangy liquid, mixing in chopped garlic, scallions, and a spoonful of chili sauce.

Dipped in this jiangshui dressing, the tofu lost all trace of beany sharpness. The acidity turned brighter, while the tofu’s delicate texture remained. It was unexpectedly delicious—surely the most authentic taste of Yulin tofu we could have hoped for.

Over the next two days, we dropped by several other Yulin tofu stores—some at roadside, some hidden in neighborhoods. Nearly all stores kept to the tradition of making fresh tofu each day. And every time stepping inside, we are greeted by the unique sour fragrance of jiangshui.

It’s the smell of heritage of tofu-making, and now, for us, it has become a part of what Yulin itself tastes like.

Leave a comment